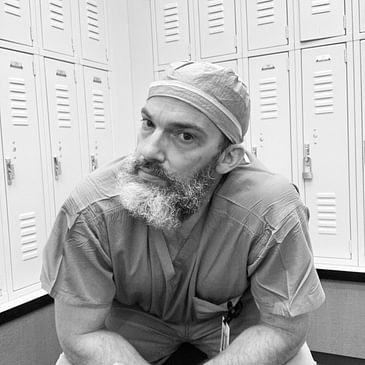

In this week's episode, I had the pleasure of interviewing D.D. Finder, aka, Delta Delta Finder. D.D. has had a remarkable 20-year healthcare career which has taken him from the Peace Corps to an EMT, from flight nursing to the ICU, and landing in Interventional Radiology.

Now, there is a new chapter in his life: author. And what does he write about? Something he is intimately familiar with.

His debut novel, Ready Left, Ready Right gives us a cockpit view of the intense pressures first responders and flight nurses endure every day.

He brilliantly accomplished his goal of bringing awareness to the extraordinary mental health challenges that these professionals struggle with in the course of their work.

And D.D. puts his money where his mouth is. He donates a portion of his book sales to three nonprofit organizations focusing on the mental health of first responders and nurses.

I absolutely loved my conversation with D.D. He truly is one of the most insightful, compassionate, generous, and funny individuals who I want in my life forever.

In the five-minute snippet: Prostitutes or batteries? You tell me! For D.D.'s bio and book recs, visit my website and the links below.

D.D. Finder website

Ready Left, Ready Right on Amazon

First Responders and Mental Health- Psychiatric Times 2022

First Responder Suicide: A Call to Action-CDC

The Overwatch Collective Instagram

Debriefing the Front Lines Instagram

62 Romeo Nonprofit Instagram

D.D.'s writing Spotify playlist:

Music for a Nurse on Spotify

Working for a Nuclear Free City, The Tree on Spotify

Rusty Nails by Moderat on Spotify

What You Want by the John Butler Trio on Spotify

The Oil by Hans Zimmer on Spotify

Don't Stay Here by Frames on Spotify

That Home by Cinematic Orchestra on Spotify

Contact The Conversing Nurse podcast

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/theconversingnursepodcast/

Website: https://theconversingnursepodcast.com

Give me feedback! Leave me a review! https://theconversingnursepodcast.com/leave-me-a-review

Would you like to be a guest on my podcast? Pitch me! https://theconversingnursepodcast.com/intake-form

Check out my guests' book recommendations! https://bookshop.org/shop/theconversingnursepodcast

Email: theconversingnursepodcast@gmail.com

Thank you and I'll see you soon!

[00:00] Michelle: In this week's episode, I had the pleasure of interviewing D. D. Finder, aka Delta Delta Finder. D. D. has had a remarkable 20-year healthcare career, which has taken him from the Peace Corps to an EMT, from flight nursing to the ICU and landing in interventional radiology.

Now there's a new chapter in his life: author. And what does he write about? Something he is intimately familiar with

His debut novel, Ready Left, Ready Right, gives us a cockpit view of the intense pressures first responders and flight nurses endure every day. He brilliantly accomplished his goal by bringing awareness to the extraordinary mental health challenges that these professionals struggle with in the course of their work.

And D. D. puts his money where his mouth is. He donates a portion of his book sales to three nonprofit organizations focusing on the mental health of first responders and nurses. I absolutely loved my conversation with D. D. He truly is one of the most insightful, compassionate, generous, and funny individuals who I want in my life forever. In the five-minute snippet: Prostitutes or batteries? You tell me. Well, good morning, D. D. Welcome to the show.

[01:44] D.D.: Thank you, Michelle, for having me. I am so stoked to be here. Anytime I get to sit down and talk to a NICU nurse who's done it for, I think, 36 years and now is having a podcast that I think is ultra important for our profession because this is what we need. This is how we are going to evolve our profession to the next step. So thank you for having me.

[02:06] Michelle: Well, thank you for those kind words, and it's really my pleasure. We met on Instagram, and you had sent me a really kind DM just saying that you had been listening to my podcast, and you gave me a little bit of your backstory, and I immediately started following you because I thought, wow, this guy is so interesting, and he's an author, and he has all this history as a nurse and EMS, and we'll get to all of that. But thank you so much again. It's really my pleasure to do this, and it's really my pleasure to talk to you. So thanks for coming on.

[02:51] D.D.: Can't wait. Looking forward to it.

[02:53] Michelle: Yeah. So let's start by, you have a very colorful bio. So that was the other thing. When I read your bio, I was like, oh, my gosh, what has this guy not done? And you gave me a little bit of your backstory. So why don't you share that with our listeners today?

[03:13] D.D.: I've been in healthcare for 22 years, been a nurse since 2010. I've been a flight nurse, ICU nurse, step-down, or a sack floor nurse. But before nursing, I was a Spanish interpreter. Before that, I was in the Peace Corps from 2001 to 2003, and that was my first experience in healthcare. Shortly after Peace Corps, I continued to live and work down in Guatemala and Honduras as an executive director of a nonprofit organization. What we would do down there was, we'd provide surgical services to families that could not afford it. So there would be doctors and surgeons that would fly into Guatemala and Honduras from Canada, the US, Europe, and even Cuban surgeons as well. And they would provide their services for almost free. What my nonprofit did was to bring in the patients that lived in very rural areas into the hospital, provide all the groundwork that would take, and then we would provide and help with the convalescence after those surgeries and bring them back to their villages. So I did that for a bunch of years and I was getting pretty big down there in the sense that I felt like I was making important decisions that would affect the health of the communities that I was serving. And I had no background in medicine. I couldn't tell you what systolic blood pressure meant, I didn't know what diabetes meant. And there I am making these big decisions. So I decided to come back to the United States. At first, I didn't know if I wanted to become a PA or a nurse. Even though half of my family are nurses, I still was looking into the best route and fell in love with the idea of becoming a flight nurse. And for whatever reason, I think I might have seen a helicopter fly over and was intrigued by it and heard that there were nurses in that helicopter. So I dedicated the next almost 14 years of my life to becoming a flight nurse and then being a flight nurse. But I had to step away from flight nursing, which I'm sure we'll get into because of the extreme amount of sleep deprivation that I went through and also working in a hostile work environment. And those two factors drove me out of what was a huge passion of mine to the point where I almost left nursing completely in healthcare. But luckily, two years ago, I found a job working in IR, and that's where I work today.

[05:45] Michelle: Okay, well that's a lot. There are some things that I would love to know a little bit more about. So your job in the Peace Corps, you're young, you are in sort of a power role. You're working with medical professionals that are providing this surgical care, medical care to people that are indigent or they just really need it. I just think that in and of itself is amazing. I interviewed a nurse a few weeks ago who goes on medical missions and does exactly what you're talking about and that's just so admirable. And I'll tell you, as I told her, one of my brothers, my late brother Joe, was a surgical nurse for many, many years and went on medical missions to Mexico and just absolutely loved it and just described it always as just life-changing. He just really couldn't put it into words, but it was life-changing. And I imagine you saw that on the patients that you treated that you were involved with. So you're working with these medical professionals, but you have no medical experience, and then you just know, I need to up my game. I need to know what we're doing here. And then you come back to the US. And was your first job as an EMT?

[07:28] D.D.: Yeah, my first job when I came back to the United States was as first medical job, I should say my actual first job when I came back was Spanish substitute teacher at the high school that I almost was kicked out of. So it was cool to give back to my own high school and a subject that I hated in high school. I absolutely hated Spanish. And luckily, when I went to college, my first degree was in environmental geoscience, which I never did anything with. So it was a bachelor's degree, and you have to take Spanish or another foreign language, and I took Spanish, and I had fantastic professors that provided me this experience that Spanish could actually be a really cool thing, and it can open up your doors in so many different avenues. And I studied abroad my junior year in college and almost didn't come back. It was like the day that I had to come back to start my senior year is when I came back. And even then, I didn't want to leave Ecuador when I lived, but that just drove me down this path of, like, I absolutely love Spanish living in Latin America, and I want to continue working there, which is what drove me to Peace Corps and then eventually working in the nonprofit world. But when I came back to, sorry, that was a little bit of a tangent, but when I came back to the United States, I didn't know if I could handle going into medicine. I had an incredible amount of doubt in myself. I actually had to almost relearn English. I was taking Spanish verbs in the infinitive verb of the verb, and I would put an English ending on them. So I was talking Spanglish, and I would have a tough time trying to word search or form a grammatically correct sentence. And I'm from the Boston area, which is difficult anyway, just growing up there, and the accent can come out once in a while. But I wanted to take a baby step into medicine, and for me, that was becoming an EMT basic first. If you want to go into medicine, I think it is the absolute best way to get an extreme amount of experience very quickly with very little training. And I'd say that unfortunately because I think EMT basics should be trained more. It was only a three-month course when I took it. Met twice a week. And then after you pass your cert, you were out on the street in some of the most insane situations you can ever imagine. To put that type of responsibility on somebody, you're quickly going to find out if medicine is for you or not. So that's why I chose that route, and I quickly learned that I can do this. I like it. I'm motivated by it. I want to learn more. I'm not just satisfied with this limited knowledge that I had. I was very thirsty, so I thought about maybe going the paramedic route for a little bit but decided that really, I needed to become a nurse. I wanted to become a flight nurse and eventually moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, went into UNM down there, university of New Mexico, went to nursing school, and graduated there, which I absolutely loved UNM at the time. You don't think you're getting a good education, and then when you leave there, you're like, wow, that was actually a really good education that they gave me. I think I was their problem child, though.

[11:07] Michelle: So working as an EMT, you are in the Boston area, and you're working in some really tough you know, you'll have to give me some frame of reference because I don't know Boston. And so you said you have three months training, and now you're just out there and you're doing your thing. And in those three months of training, was there any discussion? Was there any instruction? Was there any didactic about what you might encounter on those streets doing your job in terms of traumatic experiences and how to deal with those things? Was there any talk about that?

[11:56] D.D.: No. Just like nursing school, I mean, absolutely zero of, hey, you're going to see some horrible shit. And these are the things that you might want to consider that you should do after this call. And I see nursing students now, and I asked them that too. What are they teaching you in nursing school as far as when you have a critical stress incident? Is there any type of debriefing that you're doing? And the majority say no, so it was even worse. 2007, 2008, 2009 around that time, there were absolutely none. So you'd go in. I remember my first call was one of my first calls, I'd say, like, traumatic call was just walking into a house and seeing an elderly man slumped over dead on his table with a tiny little dog whimpering by his side. I mean, just even thinking about it gets me choked up. But there's no blood and guts everywhere. There was no family members screaming. It was just the sight of this man that I have no idea what his background was. He could have been a World War II vet. He could have been a teacher. He could have been a nurse. You don't know. And he's by himself in this very cold house with this little dog by side, and there's nothing. You go in there and you're like, yeah, he's dead. We're not going to resuscitate him. We're not transporting him. He's been dead for at least a day, maybe two days. We're not sure, but we're not transporting him. And then you leave and you go on your next call. It's similar to being a nurse where you walk into a room, you help a patient in the ICU who's on end-of-life care, and you're surrounded by the family. You help this patient pass, which can be an absolutely gratifying type of experience because it's just an honor to be with a family and help someone that has suffered for so long to go to the next experience. But you leave that room, you scrub your hands with some alcohol, and you go into your next room. And that's a patient that's possibly on a ventilator or who needs to be excavated in a totally different scenario, but yet that experience. What just happens 2ft away in the next room you're trying not to bring with you into that room that you're in now. So where does it go? Goes deep inside, and it just stays there and just like being an EMT or a first responder, first responder and nurses, we are so similar. And that's one of the things I hope by talking about this, is that nurses and first responders, we gel together more because the crap that we have to deal with as a nurse is the same stuff that you have to deal with out in the streets. We see a lot of trauma, and we internalize that trauma, and we're not trained on how to deal with it.

[14:55] Michelle: Yeah, I agree. And I would like to just go a little bit deeper into that because I was looking at some stats, and this came from an article from Psychiatric Times 2022, First Responders in Mental Health. And in it, the authors stated that an estimated 69% of EMS providers report not having enough recovery time between traumatic incidents. And you say that in your book, which we'll get to in a little bit, but there was a paragraph in there, spoiler alert, after the baby died and where you say, what do you do with that? This baby just died and we got to go on another call. First of all, we just accept it as first responders, as nurses, as medical professionals. It's just kind of part of what we do. We have this patient load, and, yeah, someone else might take over your patients for a very brief period of time while you're with another patient that's passing or that has just died. And then it's just like, okay, back to work. You got to jump right into this other situation. And I just can imagine that as an ICU nurse going from one sick, dying patient to the next really sick, dying patient and doing that for 12 hours and multiple days a week. And they were saying that in this article too, that an estimated 30% of first responders develop behavioral health conditions, including, but not limited to depression, PTSD, and the normal population suffer those around 20%. So what can we do in healthcare to give the providers, the nurses, the physicians, the first responders, the firefighters? What can we do to give them space to process these traumatic events so that we don't shove it deep inside and it doesn't affect us in the long term. What we can do and what we haven't been doing?

[17:35] D.D.: We could talk about this for hours. And I bet you have some experience in the NICU as well, maybe passes what your team did about it or didn't do about it. And also the answers are going to be different, what nurses can do and what first responders can do. I think there's slightly different answers, but it comes down to a few things. One, educating nurses and first responders. There is going to be times where you can't process the incident that second, because there's somebody out there that needs you. You have a traumatic call as a first responder. Hopefully, if it is a really bad call, they take you out of service and they bring you to some type of it could be a psychologist. It could be someone trained in that area that you can talk to right there, or even having a team member that can just debrief about it. Let's sit back. Let's just talk about this for a little bit. So you're out of service. Well, taking an ambulance out of service is also kind of like taking a nurse off the floor who's going to take over for your patients, or in the first responder world, who's going to take over for that area. So then it comes down to administration on both levels saying, well, we need to have proper staffing for these incidences, because it's not if it's going to happen, it's when it's going to happen. It's going to happen. If it's in the ICU. It might happen every shift. There might be an incident where a patient dies, sometimes unexpectedly, and sometimes it's expected and almost welcomed by the family. But that still takes something out of you as a nurse, especially if you're not prepared for it, which goes to the second part of, well, how do you prepare for it? It starts when you are in EMT school or paramedic school or you're in nursing school, and they have a curriculum that is designated to provide you the type of weapons that you need in your arson to deal with this. And there's so much you can do. There's therapy, there's writing, which is what I do. I do a lot of writing. There's people that drive into their faith that they're able to go down to the chapel and sit and pray. There's exercise. There's getting outside. There's all these things that we can do besides just bottling up. But we're not taught any of that. There's breathing techniques, there's tapping techniques, Debriefing the Front Lines, one of the nonprofits that part of the proceeds of my book will go to, they have critical stress or critical incident debriefs, where you not just talk about, but then you can learn techniques that you can do in that moment, because PTSD, your body doesn't know the difference between something that's real and something that happens. Your body is going to respond the same way. And when it does respond that way, there's things that you can do to help you in that time. We're not taught any of that. So I think one of it is education. Having podcasts, having people on social media that talk about it, that hopefully down the line during school, paramedic school, flight school, paramedic school, nursing school, sorry, they teach you these techniques. And the other big thing that, man, I would love to see is just proper staffing taking somebody off the floor, taking that ambulance out of service, giving them the time that they need to process it.

[21:21] Michelle: Yeah, those are all really great interventions, and I feel like we need to prioritize those for our profession, because where we're going right now, we just have a lot of really traumatized individuals that are leaving, that are suffering, that are taking their own lives because they don't have the tools that they need to process it. And another point that was making in this article another point that was made in this article is that there's limited culturally competent mental health resources for first responders and nurses mental health needs. And so they're saying that we're usually sent to just general mental health practitioners. And I'm not saying that those people are not qualified, but maybe they don't understand the unique demands that are faced by first responders, critical care nurses, and they don't really know how to help them in a deeper, meaningful way.

[22:36] D.D.: So true.

[22:38] Michelle: The other thing that goes along with that, and I need your opinion on this, is that healthcare workers, we consider stress to be part of the job. We know that is going to come with the job. And so a lot of us feel like we can't talk about these stressful or traumatic events. But what do you say to people who say, you chose this job, you knew what you were getting into, don't complain about it?

[23:08] D.D.: Yeah, by the way, this is a great topic. I just quickly want to say that you're absolutely right. If you are a nurse or a first responder and you want to go and seek help, they have to have experience with nurses and first responders. You can't go and sit in front of somebody and they're starting to break down and cry because you're explaining this traumatic situation. They had to be well rehearsed in our field. And so word of mouth is important. Doing some investigation about who you're sitting down in front of and asking them, do you have any experience with nurses or first responder or military that I would say would correlate to our world as well?

[23:54] Michelle: Yeah.

[23:55] D.D.: And if it's not, move on. This is like dating. If this is not the person for you, you move on. And then when you do find the right one, you go to that person. As far as what do you say if somebody says, well, this is your job, you chose this profession and this is why your podcast and other podcasts out there that we need to express what the job is really like because this is clearly somebody that has no idea what the job is like. It's not something that we choose to go and have PTSD or Insomnia or even worse thoughts of suicide or acting out on it because of horrible incidences. It's like telling the person, well, my childhood was a little bit rough and I didn't choose that childhood that was given to me and I chose nursing. But some of the rough stuff that happens with nursing is not something that I necessarily choose to be. I don't tell a truck driver that gets in an accident like, well, you chose your profession. Sucks about crashing your truck there, buddy. That is just completely a cold statement that that person could say and they just don't have any idea. So talking more openly about it. And I think having there's ways to educate people and I think one of those ways is through entertainment, which is one of the reasons why I wrote a book is I wanted to provide something out there that will subconsciously get to individuals who are not familiar with our profession in a way that is entertaining, that might open up their eyes about, oh, wow. I didn't realize how much stress you guys go through or PTSD, how relevant it is in your profession. And we need more of it, we need more people to talk out about it.

[25:54] Michelle: And I think you did that expertly well in your book and we're going to get to that. It's right around the corner because I have so many questions about it. Again, I wanted to get your opinion on this to see if you have any experience with it. So I watched Robert Sweetman, who is the founder of one of your nonprofits, 62 Romeo, and I listened to his episode on the DTD podcast, I can't say tha and I'll put this in the show notes. But one of the things that really jumped out at me was talking about living in a city as a first responder where he had attended trauma calls and driving past certain geographical locations where a baby died, a shooting occurred, a DUI accident with multiple casualties. So first, going on those calls and experiencing that trauma and not really having the tools to deal with it, to know what to do with it, and then living in the city and being part of that community, being part of that city going around and as he's driving, saying, oh, that's where that baby died. That's where that shooting happened. And then experiencing the trauma, the PTSD all over again. For me, it was inside the hospital. Like, that was my geographical location. Right? As a Peds nurse, the first time I put a child in a body bag, that was room five. But the next day, there's a new kid in room five, and I have to go in and take care of that kid. Same thing with the NICU, room 23, close to the nursing station. That's where we would put all of our super critical kids. And so those kind of things kind of help bring it back up again. Did you experience any of know working as a nurse or working in Boston as an EMT? Can you speak to that at all?

[28:12] D.D.: Absolutely. Yeah. That's a very accurate description. I have those rooms as well in the hospitals where that was the room that epic code happened, or that was the room my first code happened in. So just imagine if you lived in a hospital and every room has a story and you never really leave that, which is why first responders and cops, I think the preference is to not work and live in the same community, which is what I did when I was an EMT. I lived in the outskirts of Boston, but I would work in the inner cities that were around Boston. Up in the north part, Revere, Chelsea, Somerville. People are familiar with that area. Revere and Chelsea was really hard area. And yeah, if I were to walk down some of those corners in Revere and Chelsea, I would be reminded, yep, that's where that kid got stabbed, right there. But now I don't live there, which is thankfully, I don't have to see that. I don't have to be reminded of that. If you work in a hospital, though, you are still reminded of those things. And what do you do about it? You go and do therapy. You do the things that you need to do to get it out so that it becomes less of a you're relieving this traumatic experience every time you walk past that room because you addressed it, where if you didn't address it, then it will boil up. So if you had a patient that passed in room 15, if you didn't do anything about it, every time you go past room 15, you're going to have that feeling. But if you addressed it, that feeling won't be as paralyzing. It just might be a quick thought and that's it. And you're able to move through that thought and move on. And if you're not, another example of this would be think of something very hard to talk about. If you haven't talked about it, you're going to get choked up about it. It's going to be tough to spit out or if it's something that you have addressed, whether through therapy or the other modalities of dealing with an incident, if you have done your best to address those issues, it's going to be easier to talk about it where if you only childhood trauma for example. I've had some incidences in my childhood that sometimes it's tough to talk about, but if the more I do talk about, the easier it is. I think that's kind of the metaphor that you can use for first responders and nurses, that the more you attack the thing that is attacking you, the easier it's going to be deal with, the easier it is maybe to go past that street corner or go back into that room 15.

[31:04] Michelle: Yeah, definitely. Talking about it as you laid it out, that's really key. And I was thinking back to debriefs and nurse for 36 years and early in my career. So in the 1980s we actually had debriefs and I was kind of thinking about that. Like there's a lot of more press now about debriefing after these traumatic incidents. But the debriefs back then in the 80s were like it wasn't a debrief to talk about how you felt about the situation. It was kind of debriefing about, well, what did we do right, did we intubate at the right time? Did we give the right meds? It was debriefing about the clinical situation. So you have all these people in the room that are talking about this code that had a bad outcome and kind of what we did right and what we could have improved upon, which those things are great to do right, like that's how we learn. But nobody was discussing the elephant in the room, the emotional trauma that everybody was feeling about losing this three year old. And so as my career progressed, I did thankfully see those changes come about in debriefs because we continued to do them, but then they became more of like, we need to talk about the emotional aspect of this. So I was really happy to see that. Thinking back in your career, did you have debriefs early in your career as an EMT? Talk about that.

[33:05] D.D.: Not once as an EMT, not once. If it was a debrief, it was a snarky debrief. Dark humor would come out right away. As a flight nurse, we would debrief after every call and the debrief sometimes were really quick. If it was a non eventful call, a simple intra facility transport, nothing major happens. Just, all right, anything we need to prove upon anything we did good, anything you did bad, and then we move on. I mean, it could be a minute or two, but if it's a really bad call, then we would debrief about it. But it was just us. It wasn't necessarily someone who's really qualified to talk or to lead a debrief. However, I think that is dependent on where you work. I think there's going to be some flight companies out there that will call somebody in, possibly the area managers or the equivalent of the charge nurse, the chief flight nurse. They might have more experience debriefing, I hope they do, where they can not just talk about where the goods and the bads but how do you guys feel about this? I hope that's happening more. We had a code two weeks ago in the IR that was a rough one, and we had a debrief about it. And these are all when you work in the IR. IR, by the way, is just a hidden gem in the hospital. If you're getting a little bit burned out and you're like, you need a break from the ER or ICU, people think PACU or Cath Lab, but I think IR just smokes both of those floors. As far as better work life balance, there is still some cool stuff you do, but it's not over the top like it is in the ER or ICU. So much diversity but so we did have a critical incident, though, two weeks ago, and we had a patient we had to do CPR on, and we are sitting in a room and everyone in that room is extremely experienced. ICU and ER nurses have been doing it for decades, and I've been in the game for a long time, and I'm one of the least experienced nurses in that room. And even then, the debriefing session was more of the what do we do right, what we do wrong. But I was very thankful that we at least had that, and then we had the space for that other emotion to pop up and to just sit there for a second. The individual leading the debrief, my boss, absolutely love him. He is a great boss, but I don't know if they train charge nurses and unit directors or educators and how to address the other stuff, but at least just talking about it in that type of scenario, even if it's more of the clinical stuff I think starts to help the process as opposed to not talking anything at all about it.

[36:08] Michelle: Yeah, we were really blessed to have a clinical nurse educator that was very intuitive. And first of all, she's super smart, which most CNS are, right? But she also understood the emotional impact of losing a baby or losing a mom and was very good at leading these debriefs where we could actually talk about our feelings, and that was really helpful. And man interventional, radiology. That's a sweet spot, right?

[36:50] D.D.: It is, yeah. Oh, my God. There's like 900 reasons why I love the job. Little things. Like, one, I don't have to clean my own scrubs anymore. That was just always such a pain. You come home with a C-Diff patient and then you're just trying to isolate your scrubs from your family, your dog, just everybody. So you're just putting on the ugly green scrubs and you're throwing them in the laundry. At the end of the day, you get to listen to music while you're working. A patient comes in with a problem and leaves with an answer, as opposed to a lot of times we're just kicking the can. At least in critical emergency care, you're just kind of kicking the can down the street. Sometimes you have that GI bleeder come in. It's that typical example. They come in with GI bleed, you fix it and they go back out to drinking and they come back in again. We do about 70 different procedures in IR, so there's so much variety there, and a lot of the procedures that we do, they are we're going to fix this thing right here. A good example is kyphoplasties. So if a particular break in your vertebral body, we can actually put surgical cement in there and fix that.

[37:57] Michelle: Wow.

[37:58] D.D.: Yeah. So they come in with horrible back pain. It's this one area in their spine that we can fix, and they literally walk out a few hours later. It's so cool. Biopsies. We do a lot of that. So we get people in answer. Hopefully it's a good answer. Put Ports in cerebral angiograms for strokes. If someone comes in and they have a stroke, depending on if it's in a large vessel, we can go in and take that clot out. A few weeks ago, I had a patient, was in their forties and had left-sided deficits, which looked pretty bad. Their NIH stroke scale was in the 20s. Went in, got the clot, and this was like three in the morning, by the way.

[38:42] Michelle: Wow.

[38:43] D.D.: Got the clot out and then all of a sudden their TICI score is three. They're moving their left hand again. Their face isn't as droopy. They're giving a thumbs up, they're moving away. It's like, this is awesome. That's a win right there. Get a lot of that in IR, it rejuvenates you.

[39:03] Michelle: Yeah. That instant gratification that we all love, right?

[39:07] D.D.: Yeah. I wouldn't recommend it for the new grad, though. It's a job that I wouldn't appreciate if I was fresh out of nursing school, even just had a year or two. I would recommend to somebody that I wouldn't say burned out, but it's someone that's been in the ICU or ER for a while that's very familiar with conscious sedation that has a good feel of ventilators, is very helpful, some advanced hemodynamic monitoring, because you're going to get some of that from the ICU. About 60% of your patients are outpatient, 40% of your inpatient patients, and then out of that, 40% of your inpatient, I'd say about maybe 5% or so are scary ICU patients. So it's nice to know that information when you see that. That's nice to know, like, oh, okay, they have this going on. I know what to do about it, even though I haven't seen it in so many years and I'm not as well, rehearsing it as I was. But you are familiar with it, where if you're a new grad and it's the first time you're seeing a patient that's on Levofed and intubated, it's going to be hard.

[40:15] Michelle: Terrifying, right?

[40:17] D.D.: Yeah.

[40:18] Michelle: You hit the nail on the head. You kind of sort of said under your breath, like, burnt out. But it's so true. I worked with a former ICU nurse who went NICU and then was a NICU nurse for many years and then was just kind of like, I need to do something else. And that IR job popped up. And those IR jobs, nurses don't leave those. They are coveted. They love what they're doing. And so this job popped up and he was like, I'm gone. And he absolutely loves it because, like you said, every day is a new day. It's never the same day twice, never the same day.

[41:05] D.D.: And it's one 10th of the stress that you had as an ICU or ER nurse. And because everybody in there is so experienced, we cherish that. We know what it's like to work those long hours in those units for years on end at a time. So it's a welcome change. And if I wasn't for IR, I don't think I would be a nurse anymore. I think I would be doing something else. And thank God I found it because I have so many good skills still that I can use, and now I get to also focus on the other things. How do you make somebody comfortable? We're in the back of a helicopter. You're making somebody comfortable by probably pushing Ketamine or Versed or Fentanyl, but you're not using any of your human skills in the sense of looking at them in the eyes and seeing what they need in that moment. Is it a laugh? Is it a hug? Being able to really read that person and taking the time to explain, okay, you're a little bit scared about this procedure, but this really is not a big deal. I'm going to be there with you from start to finish. I'm going to make sure you're comfortable. I got you where? In the ICU, in the ER, you're just constantly putting out fires. You don't have that time to help those people that need that. It's not really the situation for it. So giving back to being able to stay in the profession and still use my skills, in that sense, it's been nice.

[42:37] Michelle: Yeah. I mean, IR is just like, it's all skills, right? It's people skills, it's clinical skills, and it sounds like it's really the perfect job for you, D. D. I'm really happy that you found it and that you did not leave the profession.

[42:55] D.D.: Thank you. It's a good job. I can't think of my life and I look at my life in two to five-year segments. I'm like, I know in another two years, I'm still going to want to be there. I don't know if I'm going to want to be there in another five years, but I've never been able to look past two years just how I am. But I do want to say, though, for the nurse who is listening, who is thinking about another place that they want to work, don't overlook IR. If there is an opportunity to go shadow a nurse down there, do it. See how happy they are or how unhappy they are. It's a hidden gem in the hospital. That's all I can say. But please take a look at it.

[43:36] Michelle: I love it. Well, guess what time it is? It's time to talk about your book.

[43:43] D.D.: Right on.

[43:45] Michelle: Ready Left, Ready Right. I love the title. I love the book cover. I'm one of those weird people who buys books because I like the cover. They say you can't judge a book by its cover, but I say that's bullshit.

[44:02] D.D.: Yeah, we do, though.

[44:04] Michelle: We do. And I've picked a lot of good books by the cover. So first of all, I really want to thank you for writing a book like this, because it just, like I said earlier, you expertly laid it out of what it really is like. And I'm not a flight nurse, obviously, but as a NICU nurse, I got to see you guys come into my facility in all of your glory. You guys were like heroes, coming in with all your gear, with your flight suits, and we heard the banter between you, and we would joke around with you guys, too, and just so much respect. And then my sister became a flight nurse, and I interviewed my sister on this show, Jennifer Caposella. I think she was in episode three. So it was very early on when I was just interviewing my family members, but just the utmost respect for her. And so living vicariously through her hearing about the calls she went on, the people that she worked with, and then I read your book, and I was just like, wow, I'm just reliving this all over again. This is so cool. So thank you. And at what point did you say, I'm going to be an author? I'm going to write about this. Was it something that you just did abruptly, or was it something that you worked up through, like through journaling? Talk about that.

[45:51] D.D.: Yeah, I've been writing since third grade. By the way, the episode with your sister is awesome, I listened to it. Yeah. You need to go back. You have so many good episodes, by the way.

[46:03] Michelle: Thank you.

[46:05] D.D.: One of my new favorites was John Silver's episode. Did you have John Silver recently? Yeah, fantastic.

[46:11] Michelle: Super guy.

[46:12] D.D.: Oh, my. Just that motivated might I think I'm going to have to go back and listen to it again. There's just so many gems in that.

[46:18] Michelle: Real change, real change of the profession. Right?

[46:25] D.D.: What you're doing and what I'm trying to do with this book is that I think that our profession needs these five things. We need educators, advocators, influencers, innovators. And then the fifth one is entertainers. And I think that's how you change an idea about something is that if you can entertain someone who had no idea what flight nursing is about, then they're going to start thinking about the profession in a different light. It's like when I was in middle school, I think it was, I think it was middle school or first year in high school, Boys in the Hood came out, and Boys in the Hood as a white kid growing up in the suburbs of Boston, I didn't know about inner city LA. Or really anything inner city. And that movie opens up my eyes to what it's like in another culture. And then from there, I was like, well, you know what, listen to some of more rap music and some of the music that was coming out at that time. So that opened my eyes up to a different culture. And I think entertainment can do that, and I hope this book does in that sense. And I started writing Ready Left, Ready, Right, a few years ago. It did start off as journaling, but I've been writing ever since I was in third grade. I remember the first book that I tried to write was Bugs Bunny was trying to find the Easter Bunny, and he and Elmer Fudd went out on this adventure to go find the Easter Bunny. And I just remember writing and writing and writing to the point where I never even turned it in. But my third-grade teacher was just like, just keep writing. You'll need it turned in. Just keep writing. And I think I have that story somewhere. Oh my God, my mom's house. I would love to find it.

[48:04] Michelle: I would love for you to find it. That would be awesome.

[48:09] D.D.: Now it'd be different. I probably would add a lot more character background to it. It would be a lot more probably dark as well. So a few years ago, one of the things I've been doing for the last, actually, I should say 20 years, is journaling. Anytime I would have a bad incident at work, which started in Latin America, I would just write about the incident. And it was pretty much straight up the details of it. So the sights, the sounds of some of the traumatic stuff that I've been through, and funny stuff too, I would write out. And I found that I really enjoyed it, and I continued to do that. I took a little break from nursing school because nursing school, you are still writing. You're just writing these bullshit APA papers. So I just didn't have time to really journal in nursing school. And when I got into nursing school, I did it a little bit more during the ICU. But then I went back to it pretty heavily when I became a flight nurse, especially down in New Mexico and the Albuquerque area. Over the last four years, my journaling started to realize, like, I just really like writing. I started writing short stories that were fictionally based off some of the calls that I ran. I just know it'd be interesting. I saw a AAA in the hospital, ran this call, AAA patient. And then I just wanted to take the feelings of what it was like to be in that room, but just to make a completely different story out of it. So then some of my journal entries became, like, these fictional stories. And one of my favorite movies is Dumb and Dumber by the Farley Brothers. And when they write a movie, they take really good scenes and try to link them together. So let's just write two funny scenes or three funny scenes, and we're going to link these together and make a movie out of it. And I looked at my journal entries, and I looked at these short stories I was writing. I was like, I can fictionalize all of this and write some new stuff and just link these all together. And that's when the idea started to happen, where I made writing almost a part-time job, where my days off, I would start the first two to 3 hours down in the basement in this little writing room, and I would just start writing. And about a year into that process, I was like, I got something here. I can make this a book. That's when I started telling people, yeah, I'm writing a book. But I was so far away from the end goal, and over the next it took about four years from that moment where I realized, I think I can make this into a book, into, oh, my God, I got a book now to I can actually write a second and third book. I have so much material here.

[50:53] Michelle: I love to hear the process behind authors and how they do it. And I think the general public doesn't realize how long it takes, first of all, to write, and then second, the publication. And so what was the path to publication for your book? Did you self-publish, or how did that work?

[51:17] D.D.: The path itself, there are two paths. You can do the independent route, or you can do the traditional route. I thought about doing the traditional route, but one of the things that I want to do is I want to give back to our profession. I want to help the men and women that got me up and over the pinnacle point of my career and are still in my life. I want to pay homage to these people. If I go the traditional route, traditionally, if it gets published, which is a tall order, you make less than a dollar than a book. You sell the traditional route.

[51:47] Michelle: Wow.

[51:47] D.D.: I've heard around $.60 a copy. So they will fork over a certain amount of money, let's say five grand, and through your book sales, you pay back the five to ten grand of the money that they upfronted you, and then after that, you get only a certain percentage of the book sales. So it's very little profit that you will ever see. And you have no say on the marketing, which you have no really say on the book cover. You don't really have a lot of say in it from my limited understanding of the traditional route. So automatically I was like, no, I don't want to do that. So I started looking in the independent route. I went through my word publisher, shout out to them, a guy named Brian Cancer over there who became my project manager, took me through the steps of you have a book. You have an idea for a book. I should say, now, let's publish this. And what are all the steps? I think he came up with something like 170 steps to get it published, but to do it the right way, where you look at the book and you feel it and you read it, and it is like a traditionally published book, because you can go very cheap on this today. You and I, we can just write a story together, and we could publish it by the end of the day, and we have a book. But to do it right takes a lot of steps. So I reached out to somebody that knew those steps and went through that company to help me through that process. But by doing it independently, then, yes, I see more revenue per each book I sell. I think I get about, like, $3 a book, which is still not a lot, but that's about three to four more times than what a traditional book will make.

[53:32] Michelle: Exactly.

[53:33] D.D.: And now I can take a portion of those proceeds and donate some of that to the nonprofits that I want to support that I think are doing a great job out there. And now I have more control of what the cover design looks like. I have a lot of control of the marketing. I have control of who my editors are. I have control of everything. It puts everything on me. But I'm all right with that. I think we're used to that as nurses and first responders, having that responsibility of having somebody's life in your hands. Well, I'm okay with that responsibility, whereas if I went the traditional route, it just wouldn't happen.

[54:10] Michelle: Yeah, I think, like you said, we are comfortable with that responsibility. I think part of our personalities as nurses and other medical professionals is a little bit of, we like to have power. So to have that and to have somebody kind of guiding you, that's a really cool process. Do you have a favorite character to write about? And if so, why is that person your favorite?

[54:43] D.D.: From Ready Left, Ready Right, or just character in general? There's a few characters in there that really mean a lot to me, because I want to embody somebody that admired. One of the characters that spoke out to me was Levi as the flight paramedic in that book. It was his first day on the job, and he walks into an absolute shitstorm because I could think about the person that is inspiring that character, and that person means a lot to me, and I have a tremendous amount of respect for that person. So I wanted to make an absolute badass of a character that embodies what I think of that person. My friend Mike, he's a badass person. I want to make Levi a badass flight paramedic, but there are a lot of characters that know, PJ Worth was the flight medic. She meant a lot to me in that one as well. Man, those characters, feel like family and they feel like my friends, which is why I want to write a second and third book, because I need to be in that world a little bit more.

[55:59] Michelle: They felt like that to me, too. I'm glad that you said that, because the way that you portrayed them, it was just like this instant connection. And I think Levi was my favorite as well because we've all been Levi at some point, right? So we've all had to start somewhere. We've all had that deer in the headlights know, on our first day, like, what the fuck is going on? And then we all, as seasoned nurses, medical professionals, we all have worked with a Levi, and being one ourselves, we hope we have that intuition that we know what that feels like. We remember what it feels like, and we try to help that person or kind of take it easy on that person. So I just love how you developed that character. So when you're writing, are you like a squirrel? You're working on something and then a new idea jumps out at you and then you follow that idea, or are you very focused? Talk about that.

[57:21] D.D.: I love that question because I would say I'm very focused. I go in, let me back up a little bit. My goal is to write 500 to 1000 words a day on my days off. And I try to write on my days that I'm working now because I want to get a second book out sooner than later. I don't want it to wait another four years. So I'm trying to up my game. And when I write, I put on music, and music, I think, channels that squirrel brain into more focus, and also it'll create in an emotion that I'm looking for. So I will put on a song and repeat it over and over again because there's maybe an emotional component of that song that is driving me to write in a particular way. Or some of the flight scenes. For example, I put on Oceansize, Music for a Nurse. If you listen to it, to me, it sounds like a helicopter about to land. And it's also called Music for a Nurse. And I just thought that was so appropriate. And some of the lyrics on there you can't really understand. So on some of those scenes where I wanted adrenaline, I would listen to that song. On some of the more sad parts of the book, I would listen to a variety of songs Working for a Nuclear Free City. The song's called The Tree. I would play that over and over and over again. I listen to a lot of Moderat, and these aren't typically groups and bands that I would listen to. If I just want to listen to music, it's just something about their music that would drive me to write a particular way. So that helps focus me. So typically I do write. To write. I'm focused for this hour to 2 hours. I have something in my mind. I'm continuing on from the previous day. I always leave the sentence unfinished. If I'm writing and things are going well, I'll keep going, but I will walk away before I'm done writing.

[59:27] Michelle: Wow, that's interesting.

[59:29] D.D.: I want to be able to come back the next day and go right into that sentence and not have to think like, oh, man, I had a great session, but what am I going to do tomorrow? So I'll even cut it early if things are going good, not too early, so I can come back the next day and just pick off right where I went off. And then with the music in my head, that helps as well. That's nine out of ten today. It was a one-out-of-ten scenario where I'm sitting down and I'm trying to get going on the scene that I just left off and it's not working. I don't quit, though. We don't quit in nursing. We don't quit as a first responders. If you're on a call, you're finishing that call. If you're on a shift, even if it's a horrible shift, you're going to finish that shift. That's just what we're made out of. That's how we are. And writing is the same way. Writer's block does not exist. There's no such thing as nurse's block. There's no such thing as a first responder block. You are there to write. You're going to write. But today it wasn't working. So I would let this squirrel in me take over. And I have an idea for another book. Let's just start the other book and write it. So I started writing a little bit on the other book, which I think is going to be about workplace violence. The subject is really pissing me off. I want to flip that on its head.

[01:00:43] Michelle: Thank you.

[01:00:44] D.D.: Yeah, I want to make a medical thriller out of that. So I started writing what the back cover blurb would be like, and then that motivated me to go back to the Ready Left, Ready Right sequel. And then I was able to go back into it and then the idea started coming out, 1000 words out in the middle of a sentence, stop. And now I'm going to be able to go back to that tomorrow without an issue.

[01:01:10] Michelle: Wow, that is a fascinating process. Yeah, I'm just in awe. I think writing in any sense.

[01:01:24] D.D.: I don't know, it could be difficult or it could be freeing.

[01:01:25] Michelle: Like you, I've journaled all my life. I keep all my journals and periodically go back and reflect on where I was in my life at that point. And I think journaling is really valuable for everybody, regardless if you want to be a writer or you are a writer. But just to hear your process, it's so cool. I have so much respect. I know that I would be the type of writer that would have to finish a thought, a sentence. I couldn't just leave it hanging and then go back. Wow, I have a lot of respect for that and your focus. And I knew you were going to answer that. You're a focused writer and not a squirrel writer. Because one of your books that you recommended is The Obstacle is the Way by Ryan Holiday. And I was like, anybody that reads Holiday, anybody that studies the stoic philosophy, that person is going to be focused.

[01:02:44] D.D.: Absolutely love that book. I need to reread that book. That's one of those books that you read it, you're blown away by it, and then you'll probably go back to it in a few years later just to refamiliarize yourself with the material behind that fantastic book. Journaling, though, like you mentioned, I think is such an important part of nursing. And also when you walk away from the career, you want to be able to look back and you're going to look back regardless. But it's going to be easy to remember the bad calls and the bad times that you had. Unfortunately, it might be difficult to remember some of the good stuff. So if you were to take the time a few times during the week and quickly journal about your experience as a nurse, it doesn't have to be sitting down for 2 hours like I do. This could be five minutes, this could be two minutes, a quick one-liner, something to just jog your memory about a patient, an interaction. Because nursing and first responders, your life is full of, I hate to say tragedies, but there's a lot of tragedy to it, but there's a lot of beauty to it. And to not remember it is sad to not remember those calls that you've been on or those times to have a journal where even if it's just one or two lines about your shift, maybe in the beginning you're writing it down because you need to educate yourself, oh, this happened today, I didn't remember that. If this happens, then I need to do that. But as time evolves, you're going. To want to remember those good times, and then maybe it'll help you process some of those sad times too. So if you're a new nurse out there, please do that. You're going to look back a few years later. If you have a journal of all your memories, it's a huge blessing. That's a gift that you just gave yourself.

[01:04:45] Michelle: That is great advice. And I have seen, thankfully, nursing schools now incorporating journaling about the students' experiences into the curriculum. And again, I think it's so valuable. And thinking back as a new nurse, 21 years old, I did a six-week residency in ICU, and my ICU nurse mentor started this journal for me, and it was just these papers out of a book. It's very small. It's like three by five. She tied it together with twine, and she wrote about the patients I took care of every day and what I did and why I had to call the doctor and how that call went and just things that she noticed about my care or me. And I have that book to this day. And yeah, it's such a gem. I go back and I read that it's usually in my times of self-doubt, just you have those periods of like, what have I done with my life? I don't know if that's normal, but it's just like I go back and I go, oh, my gosh, wow. Like that little 21-year-old nurse. These are the observations of a seasoned nurse. And it's just so cool. It's such a gem. I would love to find her and just tell her what that means to me, because at the time, you just don't know.

[01:06:33] D.D.: What a gift. If she didn't do that, you might not have remembered that time.

[01:06:38] Michelle: Yes, exactly. And I could remember, HIPAA is out the door. Of course, we didn't know about HIPAA back then, but she told me the names of the patients, and their diagnoses, and then when I reread it, I remember, oh, yeah, I remember that gentleman. So just yeah, like you said, such a gift.

[01:07:02] D.D.: I know. Floyd Harris that for every call that he went on, he would briefly on an Excel spreadsheet, write from where the call originated, from the destination, the time that it took, what the call was about, and that was it. So he has these Excel spreadsheet that is hundreds, probably over a thousand calls at this point in his career. And he's a math dude, but he's able to say quickly, he'll put it in the Excel spreadsheet if he wants to figure out how much time he's flown in the state of Colorado. I think that was just such a cool idea.

[01:07:43] Michelle: That's epic.

[01:07:44] D.D.: Yeah. So it's another form of journaling, even though it's an Excel spreadsheet, but with the details that he has on it, he even puts, like, lessons learned. And these are very quick because it's an Excel spreadsheet. So it's not going to be a lot of space to put all those things, but yeah, I always thought that was really cool.

[01:08:01] Michelle: Very cool. What do you want the reader to take away from Ready Left, Ready Right?

[01:08:08] D.D.: I think it depends on, are they a flight nurse or a flight medic? Do they have any experience as a nurse or do they have no healthcare experience? And depending on what those categories they fall into is what I want them to take away as a flight nurse or flight paramedic. Some of the best compliments I've gotten so far is that it makes people sweat when they read it because it is almost bringing up emotions that they have inside of them so I know I'm getting it right when they feel like it's at work. If you haven't flown in a helicopter, I want you to have that experience of what it feels like as you're about to land on an interstate that's been closed because of a horrible accident. I want you to have that excitement and that terror all at the same time and have that appreciation for the job that they're doing out there. In a sense, it's almost like Anthony Bourdain's Kitchen Confidential, where you're able to read it and you have a very good idea of what the job is about and hopefully it's entertaining and it's a page turner and you read this within a short amount of time because it's like the job, it can be extremely exciting.

[01:09:23] Michelle: Yeah, man, you said it right there. So I gave it to my daughter. She got into it. She's not medical. She's been around medical people all of her life, lots of nurses in my family. But she was immediately like, oh, my God, this is cool. I love this. So, man, I think you've accomplished that. And I'm sure she's not the only one. There's just probably hundreds of people that you've given the same experience, so that's so cool.

[01:10:01] D.D.: Thank you.

[01:10:02] Michelle: You give a portion of your book sales to some nonprofits and you briefly touched on those but talk about those and why you do that.

[01:10:11] D.D.: Yeah, so why I'm doing it is, I think I mentioned before, is just I want to give back to the people that got me up and over the pinnacle of my career. And there's two ways of doing that. One, to tell their story in a fictional way, and the other one, I think, is to give money to nonprofits that help first responders and nurses continue on. Since January, I've been looking on, thank God for social media sometimes. Other times it's a total curse. But through social media, I was looking at a few nonprofit organizations and there's a lot out there, but three that I came across that would interact with me regularly and also I just think are doing fantastic work. I want to donate a portion of the proceeds of the book to these three nonprofits it's the Overwatch Collective. It's 62 Romeo. You already talked about Rob Sweetman. It's his nonprofit and then Debriefing the Front Lines. Overwatch Collective is run by a few different people, but the one that's heading it's Greg Grogrin, and he is an active military and police officer. I think he's out in California. And his nonprofit is dedicated to finding and funding therapy sessions for first responders. So one of the issues that first responders have is the stigma when it comes to looking for help. And a lot of people don't want to go through their employee program. Their EPA, is it? Employee Program assistance. They don't want to go through the EAP for fear that perhaps this is going to get back to their employer. So one of the things that the Overwatch Collective does is that they find therapists within their area that are familiar with the first responder world. And if that first responder cannot afford the therapy, then they're going to pay 100% of what it costs to see that therapist for the first three sessions, 60% for five sessions after that, and then 50% for the next five. So then it's a tier system. So they're actually paying for the vast majority of those therapy sessions. 62 Romeo, Rob Sweetman's organization is all about helping first responders and soon nurses. By the way, how to properly sleep. Sounds weird that we need to educate ourselves on how to sleep. I don't need to educate myself on how to drink water and sleeping. This program changed my life. Rob Sweetman is a retired US. Navy Seal and he got out of the Seals when one of his classmates and colleagues committed suicide. And Rob thought that this Navy Seal, which unfortunately I'm forgetting his name, who committed suicide, but he was a superior Navy Seal to Rob, and that if it happened to this individual, then Rob was next and his friends were next. He decided to investigate what are the causes of suicide. And one of them is sleep deprivation is insomnia. It's PTSD, and those are all combined together. And it's one of the reasons why I've had a lot of trouble sleeping as a first responder, whether if it's a call you're thinking about or just generalized anxiety. So I went through the six-week course and learned all about sleep environments, the importance of limiting caffeine. These are all things we know, but to do it through that program, it just provides a different lens and gives a lot of insights and rules. For example, I don't drink any caffeine after noon. Now, where before I would drink cups of coffee, probably up to about 03:00, I didn't really care how much I would take the LED lights in the house. They emit blue light. Don't just think about your cell phones and your TVs. It's also the LED lights in your kitchen. So those lights, they are going to prevent the release of melatonin. That's what blue light does, prevents the release of Melatonin. And so then you're not going to be able to fall asleep because your kitchen lights have been on for the last hour. So when it gets closer to being dark out, all those bright LED lights, they come off in my house. And thank God my wife's on board with this fanatical bed routine that I have. But the three big things are light, sleep and sound. And that six-week program gave me so many great tools to battle my insomnia. And then the third nonprofit is Debriefing the Front Lines. It is a nurse-led nonprofit. Right now they have three nurses who lead it, and Michelle, Casey, and Tara. I love everything that they're, um, they take on cumulative care taking trauma is their big educational point. So they do a lot of courses to help the nurse deal with cumulative caretaking trauma. And if you just think about what that is, nurses die by 1000 cuts. We see all the little things during a shift, and that cumulative care just starts adding up and it creates more trauma within ourselves. So they provide debriefing sessions to deal with cumulative caretaking trauma, or CCT, or a single incident. So if there is a really bad incident at work, you can contact Debriefing The Front Lines. Or if you're having issues, they will provide debriefing sessions. They will give you tools to help you navigate through those difficult times in your career. So there's an emotional wellness and there's also sobriety support within that group because unfortunately, nurses and first responders, drinking and other drugs is part of dealing with what we see. And it's not the answer. I'd like a good tequila. I like a good bourbon. But to rely on drinking to get through a bad situation, it's not the answer. If anything is going to mess with your sleep and it's going to make everything worse.

[01:16:47] Michelle: Yes, gosh.

[01:16:48] D.D.: So those three nonprofits are the ones that I'm going to be supporting through the lifetime of this book. So if you buy Ready Left, Ready Right, a portion of those proceeds will go to those three nonprofits.

[01:17:01] Michelle: Well, those are some really worthy nonprofits. So you chose really well. And I really have so much respect for people who give back in that way that they've seen a need. And they say, I can fill this need with my expertise and my education. And instead of trying to make a buck, they're like, no, these people need what I can provide, and I'm going to do this at no. You know those nonprofits, they need our help, they need our donations. So that's how they keep Rob's story that I heard on the podcast talks about his friend's suicide. His friend had had no sleep for five days before he took his own life.

[01:18:08] D.D.: And we're all susceptible to that night shift workers, even non night shift workers. What do you do when you get off shift? How are you taking care of yourself. And I took Ambien for ten years. That's another reason why 62 Romeo is so near and dear in my heart. I'm not on Ambien anymore. I don't take melatonin anymore, and I still have crappy nights of sleeping. It's not perfect, but it is significantly better than three years ago. And now my nightly routine doesn't involve popping five to ten milligrams of ambient before I go to bed, but now involves meditation and breathing techniques and making sure that my sleeping environment is as perfect as it can be before I go to bed. And if it's not that night, then it will be, hopefully the next night. If it's not that night, maybe the third night. But I would go a lot of nights without sleeping, and it's just so dangerous. Imagine just not getting any sleep, or three to 4 hours of sleep on Ambien and then going into the ICU to take care of your patient.

[01:19:14] Michelle: Yeah, I did Ambien for like, a year, and that stuff will screw you up faster than anything.

[01:19:26] D.D.: You might as well drink a pint of vodka before you go to bed, because it's the same thing. You think you're sleeping, but you're not. You're not getting that deep REM sleep.

[01:19:35] Michelle: No. It's bizarre.

[01:19:37] D.D.: Yeah. And then long-term consequences of that, of taking Ambien and not sleeping. You're looking at heart disease, you're looking at Alzheimer's, you're looking at cancers. I did it for a while. If I had 62 Romeo or if I knew those sleeping techniques that we should be practicing every night, maybe my life would be different. Maybe I'd still be a flight nurse now. But it's not, and that's fine. I've moved on, and now I get to do something else and hopefully give back to our profession. And you're giving back to our profession, Michelle, as well. This podcast is so important for nurses and people who are surrounded and touched by nurses because we need our profession to evolve. And you have been in this profession long enough, or just tell me if I'm wrong, but we have evolved in certain things, and we are exactly where we were 40 years ago.

[01:20:39] Michelle: Yeah, you're absolutely right, D. D. Exactly. Like I was talking about the debriefings earlier, we certainly have evolved with that. But there are other things, like bullying in nursing continues to this day, and I experienced that my very first day in 1986 as a 21-year-old new nurse. So some things never change, unfortunately, but we need to bring attention to those things, and we need to work on those things as a profession. And thank you for those kind words. I really love what I did for 36 years, and I love the nursing profession. I love nurses. I loved being a nurse, and I love what I'm doing now. So thank you so much for that.

[01:21:35] D.D.: Thank you.

[01:21:37] Michelle: So before we wrap up, how do we find you and how do we find your book?

[01:21:43] D.D.: Ready Left, Ready Right is on Amazon. So if you just go to Amazon, it's the only place it is for the time being. I might branch out to some other areas, but it is on Amazon, and I can be found on Instagram, @DDfinder. That's Delta, Delta Finder, also my website, ddfinder.com. So if you read the book, please just hit me up. Tell me if I got it right or wrong. Tell me if you enjoyed it or not. I would love to hear from anybody out there that's any feedback would be great.

[01:22:17] Michelle: Well, it's getting great reviews, and I know that will continue because it's quality. And I encourage nurses, first responders, any medical professionals to read it. It's really educational and it's very entertaining. And you will see yourself in this book. And for the lay public, it's just a glimpse into our lives as medical professionals, and I know you'll appreciate it as well. So thank you for writing it, and thank you for coming on today to talk about it. And you know what time it is now D. D.?

[01:23:04] D.D.: Let's bring it. Let's do this.

[01:23:06] Michelle: The five-minute snippet.

[01:23:08] D.D.: Yeah.

[01:23:09] Michelle: Okay, I'm going to start my timer. And you're up.

[01:23:17] D.D.: All right.

[01:23:18] Michelle: What was the best money you ever spent as a writer?

[01:23:23] D.D.: I would have to say, and it was a good amount, but hiring that project manager to help me navigate through traditional publishing. So spending money, my word publishing and using Brian Cantor. And then the second one was actually the course that I took at Boston College was this geology course that I was in that even though it was a geology course, we would have to write 500-word essays. And that's it. It couldn't be more than that. So you would have to really condense everything down into 500 words. And that has helped me a lot. So that expensive education. Oh, yeah. That $90,000 first degree that I did nothing with was helpful in my writing.

[01:24:14] Michelle: Hey, who knew, right? Okay. Would you rather star in a reality TV show that documents your life or be the host of a popular podcast?

[01:24:27] D.D.: I don't think my wife would like me to host the reality show, but the ego inside of me would want that. I would have to go with the podcast. Yeah. Unfortunately.

[01:24:41] Michelle: I just see that in your future. I think you'd be an awesome podcaster. You definitely have the voice for it.

[01:24:47] D.D.: Thank you.

[01:24:49] Michelle: What's the most creative excuse you use to get out of something?

[01:24:55] D.D.: My wife and I always jock that. Diarrhea is always the excuse. We got diarrhea again. We just can't do it. I was in the Peace Corps, too, so that was an experience. You just had a lot of that down there.

[01:25:16] Michelle: I bet. Oh, my gosh.

[01:25:18] D.D.: Yeah. If you need to call off work and they want to know why: diarrhea. Diarrhea. You need a mental day off. You're like, I got diarrhea. I can't make it.

[01:25:27] Michelle: Good to know. Okay. Was there an early experience where you learned that language had power?

[01:25:37] D.D.: When I was learning Spanish, if I got the word wrong and I said the wrong word, like, I went into a grocery store and I thought I was asking for batteries and I was really asking for prostitutes, I realized that words matter.

[01:25:55] Michelle: Yeah, that's a good lesson.

[01:25:58] D.D.: Yeah. I started yelling, Where are the batteries?

[01:26:03] Michelle: That's what I thought I was asking, but yelling?

[01:26:06] D.D.: Well, because he looked at me, why is he asking me where the prostitutes are? And it's like, clearly I just need to over enunciate and speak louder. And that was an eye opening experience. Like, words matter. Word selection matters.

[01:26:22] Michelle: That's great. What's the one thing you'll be really disappointed about if you never get to experience it?

[01:26:30] D.D.: My wife and I were just talking about this last night. I think possibly going to the Grand Canyon and not doing the rim-to-rim hike. That might be one of those things. And it's maybe not necessarily just that hike, but getting outside more and experiencing our national parks and experiencing the things that you can do over, like in Europe or Latin America. So traveling and living life a little bit more. But right now, that rim-to-rim hike in Grand Canyons, is calling me.

[01:27:04] Michelle: I saw your post this morning on Instagram and just being outside and that little babbling brook, and I was like, oh, my gosh, I want to be there.

[01:27:16] D.D.: Yes. We'll be doing that tomorrow.

[01:27:18] Michelle: Yeah. Would you rather be a presidential speech writer or a member of Congress?

[01:27:27] D.D.: Wow. Both involve selling my soul. I would probably do the speechwriter and hope to God that it is a candidate that I actually believe in and not the clowns that we have at our disposal to vote for right now.

[01:27:46] Michelle: All right, last question. Would you rather be caught in a volcanic eruption or an avalanche?

[01:27:55] D.D.: I've been near both in Latin America. I was near some volcanoes hiked. An active volcano. Avalanche, I've definitely been near some pretty heavy snow before. Luckily, nothing. Survival rates of an avalanche are probably pretty minor, but I'm going to go with avalanche because I don't think if they're both bad, you're probably dead. So what's the quickest way to go? I'm thinking avalanche, and it's probably because I'm doing something that I'd like to do, like snowboarding. So it's dark. I don't know if I'm going to survive either or, and I might as well be outside on a mountain and having that avalanche come. But, man, that's a rough one.

[01:28:43] Michelle: Kind of a hard one.

[01:28:44] D.D.: Yeah, well, volcanoes just scare me, too. And the smell of the sulfur and all the dust.

[01:28:51] Michelle: Oh, my gosh, I can't imagine coming up that close. Yeah. Okay, I'm going to ask you one more because I didn't get to this one, but I thought it was funny. It's a would you rather, watch Bad Santa or The Nightmare Before Christmas?

[01:29:07] D.D.: Bad Santa for sure. Yeah.

[01:29:10] Michelle: That's just like this guilty pleasure. It's just total craziness, but you just laugh.

[01:29:17] D.D.: Michelle, can I ask you a question? I have to flip you on this. I have to ask because you ended on a Christmas one. Is Diehard a Christmas movie?

[01:29:29] Michelle: You know, I don't know. I've seen it, and I really don't remember a lot about it. It was just a lot of action, and it's because my late husband loved that kind of film, and so he would always pull me into it, and I really didn't have an interest, but there was some discussion on that that I was hearing, and I was like, Is it a Christmas movie? I didn't know it was a Christmas movie, so I don't know the answer to that.

[01:29:58] D.D.: I don't either. Or there are about 50/50 responses out there.

[01:30:05] Michelle: It's kind of like, is this dress blue or black? One of those things, like, what do you see? Yeah, that's great. Thank you for flipping that on me. I appreciate that. This has been so fun D. D., thank you so much for sharing your story and your purpose and your book, and I just really appreciate you DM'ing me and all the kind words that you've given me. It's really good for the ego. So thank you so much.

[01:30:39] D.D.: Well, thank you so much for having me on the show. And now I get to sit back and be a listener again, so thank you.

[01:30:48] Michelle: Well, you take care. Have a great day. Get outside. Do something fun.

[01:30:53] D.D.: Will do. You too, Michelle. Thanks so much.